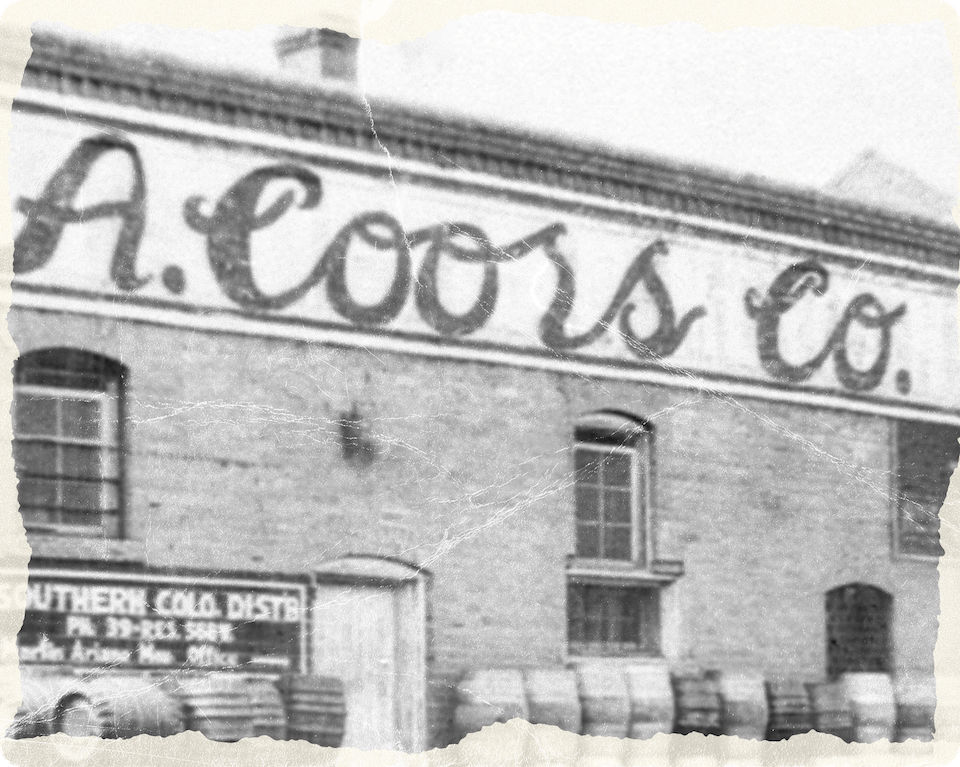

With the Coors name known around the world, it’s hard to believe that it was once a local brewery serving miners looking to make their fortune in Colorado.

When Adolph Coors Sr. founded the brewery back in 1873, he had big dreams. But time and again throughout the brewery’s history, forces outside its control threatened to undo everything the Coors family had worked for.

It’s why the company’s longtime chairman Bill Coors was near obsessed with the idea of survival, having witnessed Prohibition break his grandfather’s heart and seen the brewing industry’s struggles during World War II.

“Our long-range plan back in 1946 was survival. Now, our long-range plan is three things: survival, survival, survival,” he said in 1999.

There were five pivotal moments in the brewery’s history that shaped its future, says Heidi Harris, Coors’ archivist.

“You can point to several key moments where Coors' foresight helped get this brewery to survive for 150 years,” she says.

The flood

Things had been going well for Adolph Coors. Within seven years of founding the brewery, he bought out partner Jacob Schueler. He had taken out a $90,000 (about $3.2 million today) loan from a bank to grow the brewery. Then, in late May 1894, a period of heavy rain fell, inundating the Golden Valley and flooding the area around Clear Creek, where the brewery was (and still is) located. Floodwater ravaged the brewery and the Coors home.

“Flooding destroyed the newly completed addition (to the brewery) and carried away two ice reservoirs. The home was surrounded by flood waters,” Harris said.

To recover, Coors went back to the bank, asking for another loan – but not before vowing to never rely on lenders again.

“The family stood by that and didn’t owe anybody money until the 1980s,” Harris said.

Picket signs and pickaxes

As the 20th century rolled around, a growing movement across the country advocated for abolishing alcohol by protesting breweries, social clubs and taverns with picket signs and pickaxes.

“Adolph said, ‘We are going to survive no matter what is going to come,’” Harris says. “He knew Prohibition was going to happen.”

As anti-alcohol forces in the U.S. grew in the early part of the 20th century, Coors sought security in other industries, buying a pottery company, which led to the founding of Coors Porcelain Co. in 1910. He put money into real estate holdings, taverns and tied houses.

He sought to diversify, which proved a sound strategy given the boot that was about to step on the brewing industry’s neck.

Prohibition comes early

The 18th Amendment was passed and ratified in 1919, banning the general production and sale of alcohol in the United States.

In Colorado, Prohibition was enacted in 1916, meaning Coors Brewing Co. could not brew a drop of beer or sell its product outside of Colorado.

Of the roughly 1,300 American breweries that operated at the time Prohibition passed, no more than 100 outlasted the dry period, according to Maureen Ogle, author of Ambitious Brew: The Story of American Beer. Adolph Coors was determined his brewery would survive, and his foresight to diversify his holdings proved critical.

Coors Porcelain Co. churned out household goods, like the popular Rosebud line of dishes and cups, as well as ceramics for scientific purposes, such as sparkplugs, used by Thomas Edison, among others. (Today the company is known as CoorsTek. Still based in Golden, its products supply many industries, from home appliances to medicine.)

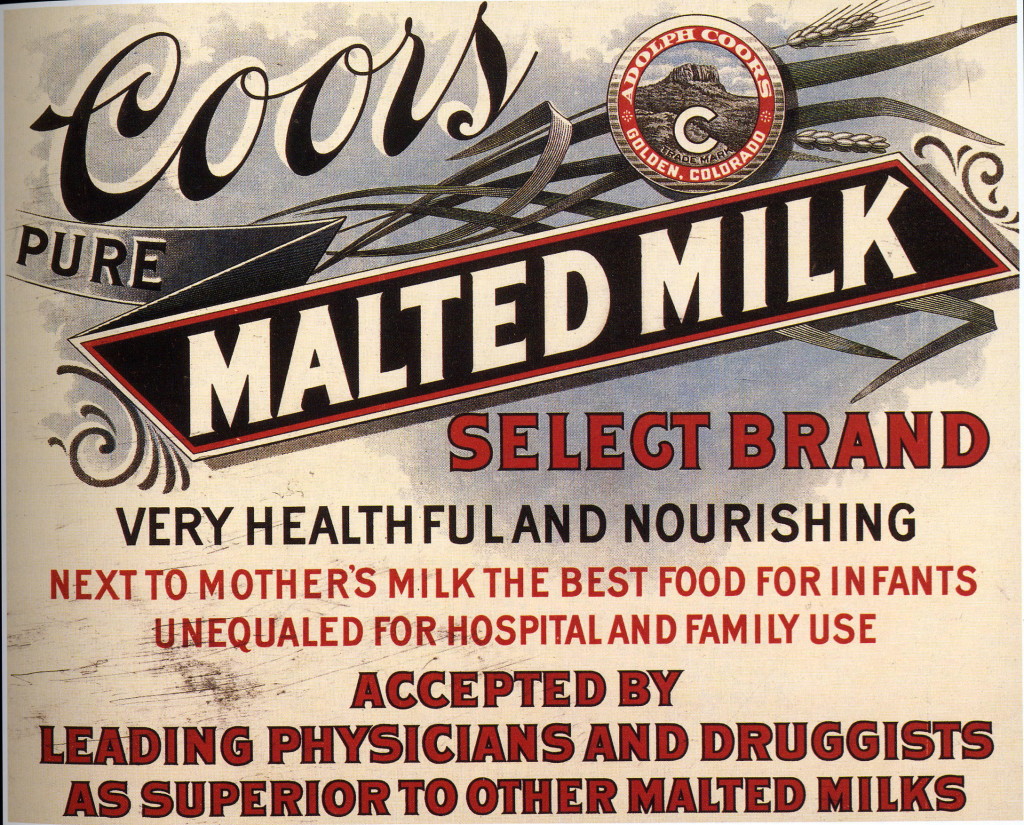

The brewery’s malting department pivoted from providing malt for beer to producing malted milk. That led to a relationship with the Mars candy company to create confectionaries.

Coors sold near beer (aka non-alcoholic beer) called Coorsal and Mannah. It sold the alcohol distilled from brewing near beer to pharmacies for medicinal purposes.

Prohibition ended in 1933 and Coors was back to doing what it did best: brewing beer.

In short, Coors’ foresight paid off. The company never made a profit, Harris says, but it survived. Yet Adolph Coors wouldn’t live to see the end of Prohibition; he died in 1929 at the age of 82.

“Between the brewery and porcelain, they were really trying to keep the people of Golden employed,” she says. “Hiring people at Coors Porcelain and the brewery really helped keep Golden alive, as well.”

The war

Having successfully withstood Prohibition, the brewery moved forward, now under the leadership of Adolph Coors, Jr. But within eight years, the world was at war and the brewery was enlisted to boost the morale of the troops, sending 15% of its beer overseas.

With the entire country called upon to use less as more resources went towards winning the war, the brewery suffered. A plan to sell a second beer called Coors (New) Light was shelved. Steel and grain were in short supply. So were people who worked in the brewery.

The hardships revealed another opportunity for the brewery, namely expanding its own supply chain.

Bill Coors soon implemented the company’s barley program, working with farmers to plant, grow and harvest a hardy strain of Moravian barley that has made up the bulk of Coors’ grain bill for more than 75 years.

As the 20th century progressed, the company brought more elements of its production in house. It built its own can and bottle plants. It established Coors Energy Company to power brewery operations. The company acquired water rights to ensure a steady supply of brewing water.

“If you think back to the generations of Uncle Bill or Adolph Jr. and you’re talking about world wars and the impact it has on your business, it was a defense mechanism. Any one of those challenges could have put us out of business,” says David Coors, executive chairman of Coors Spirits Co. “They battled through it by vertically integrating.”

New ideas

In the mid-70s, American drinkers were seeking out a new kind of beer. They were stocking up on light beers from the country’s leading breweries. But Coors, whose distribution footprint was limited to 11 states west of the Rockies, still had just one offering: Coors Banquet.

“We felt we probably couldn’t survive long-term if we didn’t have a national presence,” said Pete Coors, the brewery’s former president and a current member of Molson Coors’ board of directors. He recalls writing all the competing breweries’ products on a napkin.

“And then I wrote ‘Coors…Coors.’ That was it,” he said in a video recalling the beer’s genesis. “We decided to give it a try.”

Coors Light was born in 1978.

Coors Light was born in 1978.

Skeptics, even those within the company’s leadership team, predicted it would tap out at 4.5% of Coors Banquet’s sales. Bill Coors guessed a generous 14.5%, Pete Coors recalled.

“Now it’s 10 times bigger than Banquet,” he said, with a chuckle.

At the time, Pete Coors and his brother Jeff were newly named co-presidents of the brewery, which had traditionally paid little attention to advertising. That changed with new leadership, a new product and new approach to marketing, showcasing Coors to more diverse groups of consumers.

By 1983, with Coors Light propelling the brewery and Banquet’s cache still strong, the company posted its best earnings since its founding 110 years earlier.

“Coors needed to hit on a different audience with Coors Light. It helped show that Coors wasn’t just a one-trick pony. We could do other beers and we could do them well,” Harris says.

After 150 years, weathering dry laws and drought, world wars and light beer wars, Coors is synonymous with Rocky Mountain refreshment and known across the world. Had it not been for the grit and foresight of generations of Coorses and the employees who worked alongside them, the story might be different.

Harris says it’s due to an ethos that goes back to early Colorado settlers: “They take care of each other and take care of themselves,” she says. “And they keep things going no matter what.”